- Home

- Parnell Hall

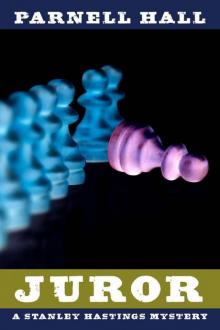

6 Juror

6 Juror Read online

Praise for Parnell Hall’s mystery JUROR

“This unlikely private detective operates in an exquisitely refined state of paranoia. . . he manages to effect a pretty astonishing resolution to the mystery. . . (the case) turns out to have a surprising kick at the end.”

—Marilyn Stasio, New York Times Book Review

“Terrific. . . You’re never, never, never, ever gonna guess whodunit!”

—San Diego Tribune

“A great book. . . hilarious. . . you’ll become addicted to Stanley Hastings.”

—Mystery News

“The last scene of the tale's approximately forty in-court pages embodies a terrific stunt payoff, and, all in all, this is a hugely enjoyable novel.”

—Jon L. Breen, Novel Verdicts, The Armchair Detective

JUROR

Parnell Hall

Copyright © 1990, 2010 by Parnell Hall

Published by Parnell Hall, eBook edition, 2010.

Published by Onyx Books: NAL Penguin Inc., 1992.

ISBN: 978-0-451403-16-2

Originally published by Donald I. Fine, Inc., 1991.

ISBN: 978-1-55611-230-0

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in whole or in part without written permission from the author, except by reviewers who may quote brief excerpts in connection with a review in a newspaper, magazine, or electronic publication; nor may any part of this book be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, without permission in writing from the author.

ISBN (Kindle): 978-1-936441-14-3

ISBN (ePub): 978-1-936441-15-0

Cover design: Michael Fusco Design | michaelfuscodesign.com

For Jim and Franny

Table of Contents

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

1.

I GOT JURY DUTY.

I know that shouldn’t sound like an earth-shattering event—everybody gets jury duty—but the thing is, I’m not supposed to get jury duty. Because in point of fact, everybody doesn’t get jury duty. Some people are exempt.

Now, I hate to say that, because it immediately conjures up a picture of an elite upper class, with sufficient political connections to pull a few strings and wriggle out of the duties and responsibilities dumped on the poor, unwashed masses. But such is not the case. Jury duty exemptions are actually based on hardship.

One reason jury duty is a hardship to some is that it pays squat. By last count, the stipend for doing jury duty was up to a whopping twelve bucks a day. You don’t have to be a math major to figure out that falls somewhat short of the minimum wage. But since jury duty is an obligation, not a job, the judicial system’s able to get away with paying it.

For most people, the twelve bucks a day isn’t a hardship. That’s because they work regular jobs and have an employer who pays them a salary, and during the two weeks of jury duty it’s the employer who takes the loss, continuing wages to people who are not there. So for those jurors, the twelve bucks a day is actually a bonus.

The people who take it on the chin, of course, are the people who are self-employed. If you work for yourself in a one-man operation and you aren’t there, you don’t earn. For that reason, anyone can be exempt from jury duty if he happens to be the sole proprietor of his business.

I’m the sole proprietor of mine. Stanley Hastings Detective Agency. Don’t get me wrong, it’s not really an agency. It’s a one-man show, and I’m him. Or I’m he, if you want to be grammatical. At any rate, I’m the sole proprietor, the sole employee, the sole source of income. I work my butt off day after day trying to feed my wife and kid. In New York City, that ain’t easy. I’m always behind. For me, to close up shop and earn twelve bucks a day for two weeks would be a disaster of such epic proportions that I might never recover. In short, I am exactly the sort of person the laws about juror exemptions were designed to protect.

So when I got my notice of jury duty, I immediately called the number on the form that you were supposed to call if you had any problems or questions. This being a government agency, I only had to tell my story four times before I finally got transferred to the right person who should have been hearing it. She was a nice woman, sympathetic and understanding. She said there was no problem, on the basis of what I told her I should be exempt, and all I had to do was come in and bring in my most recent tax record to show that I was, indeed, the sole proprietor of my business and that would be that.

So I did.

But since I started this whole thing by saying I got jury duty, you have to know something went wrong. And, of course, something did. Which it shouldn’t have. Because I am the sole proprietor of my business, and have been for several years. As I said, I’m a private detective. Not a grand and glamorous one like you see on TV, but a private detective nonetheless. I work for the law firm of Rosenberg and Stone. Don’t get me wrong—I’m not employed by the law firm of Rosenberg and Stone—my agency is. Stanley Hastings detective agency is subcontracted by Rosenberg and Stone to investigate some of their accident cases. For this, I am paid a flat fee as an independent contractor. At the end of the year I get a 1099 form from Rosenberg and Stone listing my gross earnings. From this amount I deduct my expenses and then pay my taxes. And four times a year I pay estimated taxes because I have no withholding. I also pay Unincorporated Business Tax. In short, I do everything a sole proprietor of his business should do.

So what went wrong?

Well, I wasn’t always a private detective. I’ve been doing it for the last few years, but before that I’ve been many other things. Before I was a private detective I was a failed writer, and before I was a failed writer I was a failed actor.

It’s the acting part I want to talk about. You see, twenty years ago I was in Arnold Schwarzenegger’s first movie.

That probably surprises you, because most people think Arnold Schwarzenegger’s first movie was Pumping Iron, but it wasn’t. He did another movie way before that, and the only reason you don’t know that is because nobody’s ever heard of it. The movie was called Hercules in New York. It starred Arnold Schwarzenegger as Hercules. Only Arnold Schwarzenegger wasn’t a household word back then. Aside from being Mr. Universe, which only those in the bodybuilding biz would know, his biggest claim to fame was appearing on the inside cover of Marvel comic books, standing there flexing his muscles and supporting a curvaceous, smiling girl in a bathing suit who was sitting on his bicep, as an advertisement for Joe Weider’s weight building course.

Someone, somewhere, got the bright idea that this young man should be in a movie, and damned if he wasn’t. The plot of Hercules in New York involved Zeus, king of the gods, zapping Hercules with a thunderbolt and knocking him off

Mount Olympus (shot in Central Park), and Hercules falling into the harbor and winding up in New York, and having various capers with a bunch of Damon Runyonesque crooks.

Schwarzenegger wasn’t bad, by the way, if you can imagine an Austrian actor with a thick accent, playing a Greek god in a production of Guys and Dolls. Had it been left that way, the movie at least would have been high camp. But the producers weren’t happy with Arnold’s accent, so they dubbed his voice. They also knew the name Schwarzenegger would never do, so they changed his name to Arnold Strong. This was largely because the co-star in the movie was Arnold Stang, the little guy with glasses who used to do the Chunky commercials, which made for cute billing—“Arnold Strong and Arnold Stang in, Hercules in New York.”

And where do I come into all this? Well, as I said, I had a part in the movie. It wasn’t much, but as a struggling actor, I was damn glad to get it. I played “Skinny Hercules.” I had a horse and chariot and I wore a leopard skin and I stood outside a movie theater, and the horse and chariot and I were all supposedly an advertisement for yet another fictitious Hercules movie. During the chase scene, Schwarzenegger runs from the theater, steals my chariot and takes off after the Damon Runyon-type crooks. I chase the chariot down Broadway, waving a hotdog I just bought from a Sabrett vendor and screaming, “Come back with my chariot!”

“Come back with my chariot!” Pay attention to those five words, because they are important. They were my only line in the movie. By saying them, my status in the movie was upgraded from “Silent Bit,” which at the time was seventy-five bucks a day, to “Day Player,” which was a hundred and twenty. Not only that, being a Day Player made me SAG eligible, and I immediately joined the Screen Actors Guild, in the hope that this movie might launch a few careers.

My career never took off.

Arnold Schwarzenegger’s eventually did.

But not because of this movie. No one I know has ever seen this movie. I have never seen this movie. But it does exist, and still does play now and then somewhere on late-night TV. I know this because every time it does I get a forty-dollar residual check as a bonus for having said those five immortal words, “Come back with my chariot!” and having been upgraded to Day Player status. So each time the forty bucks arrives in the mail—thirty-two something, actually, after taxes—I’m pleased of course, but I’m also somewhat wistful, when I think about what might have been.

But I digress. The point is, as soon as I found out I could get out of jury duty I grabbed my tax records and rushed straight down to do it.

Apparently, getting out of jury duty isn’t exactly a novel idea, because there were about thirty people ahead of me. After waiting for two hours, I finally found myself in a glass partitioned cubicle sitting across the desk from a crisp, efficient-looking woman, who took my juror duty notification slip, inspected it, and said, “You’re applying for an exemption, Mr. Hastings?”

“That’s right.”

“On what grounds?”

“That I’m self-employed and the sole proprietor of my business.”

“Did you bring your tax return?”

“Yes, I did.”

I opened my briefcase and handed her my last year’s tax return. I did so with absolute confidence. I pay an accountant a hundred bucks a year to fill out my tax return. I’m sure he saves me more than that, and even if he didn’t, it would be worth it, just for the peace of mind of knowing the thing had been done right, that I wouldn’t be audited and suddenly find I owed a bunch of back taxes plus penalties and interest and the whole shmear.

The woman took my tax return and riffled through the pages. She nodded her head—I didn’t know what that meant, but it looked promising. Then she riffled through the 1099 forms stapled to the top of the front page.

She stopped, frowned, pointed to one. “What’s this?” she demanded.

I shrugged. “A 1099 form.”

“No, it isn’t.”

“Oh?”

“No. It’s a W2.”

I leaned across the desk and looked. It was indeed a W2 for my forty-dollar residual for Hercules in New York.

“Right,” I said. “That’s a residual check I got for a movie I was in.”

The woman shook her head. “I’m sorry, Mr. Hastings. You don’t qualify for exemption.”

“Why not?”

“Because you’re not self-employed.”

“Yes I am. Look at my return. I run my own business. I pay Unincorporated Business Tax.”

“Yes, but you have a W2 form.”

“So what?”

“You’re not self-employed. You have an employer. This movie production company. They paid you as an employee and withheld taxes.”

“Forty dollars.”

“The amount doesn’t matter. The fact is, they paid you.”

I smiled and held up my hands. “You don’t understand. See, I didn’t work for this company last year. I worked for no one but me. I worked for that company twenty years ago. I did one day’s work as an actor in a movie. The movie played on television one night last year, so I they sent me a residual check. But I didn’t do any work for it. See?”

She saw all right. She shook her head. “If you have a W2, you’re not self-employed.”

I frowned. How quickly one’s opinions could change. I realized what I had taken for intelligence and efficiency in this woman was actually the precision of an automaton, a government employee incapable of independent thought.

“Whoa,” I said. “Didn’t you hear me? I did no work last year, except for myself. I did not work for this company last year. I am self-employed and have been for several years. Being on a jury would be a tremendous financial hardship for me. I am exactly the sort of person this exemption system was set up to protect.”

Now she got angry. How dare I question her authority? Her lips set in a firm line, and her eyes were hard. “Mr. Hastings,” she said. “Perhaps you didn’t hear me. You have a W2. You are not self-employed.”

I took a breath. So much for trying to make her understand. “All right,” I said. “Let me talk to your superior.”

I expected her to be furious, but at that point I didn’t care. I just wanted to get away from her and find a genuine human being I could talk to. A person who could think and reason.

It was not to be. The woman may have been furious, but she didn’t show it. She actually seemed somewhat pleased. She drew herself up, stuck out her chin, fixed me with her eyes, and said with just a trace of a smug smile, “I am my superior.”

I’m sure there are lots of people in the world who could have gotten past that. I’m not one of them. I was absolutely floored. Those four words stopped me dead. “I am my superior.” What the hell was it? It’s not a non sequitur. It’s not a paradox. It’s an absurdity, yes, but even more than that, you know what I mean? At any rate, I couldn’t deal with it. And I couldn’t deal with her. And I couldn’t deal with her superior, since her superior was her.

So I was stumped. And that was it. The end result was, my five words, “Come back with my chariot!” and her four words, “I am my superior,” somehow through algebra, calculus and the new math, added up to the two words, “Dorked again.”

I got jury duty.

2.

I WAS ORDERED TO REPORT to Room 362 at 111 Centre Street, which I figured to be the Criminal Court Building. My call was for ten o’clock, so I hit the subway at nine. I knew I was overprotecting, but I didn’t want to be late my first day. I rode down to Chambers Street, walked over to Centre Street, and up Centre to 111.

I could see the courthouse as I walked up Centre Street. You can’t miss it. It looks like a courthouse—a big stone building with marble pillars and long, wide marble steps. It’s the one you see in all the courtroom movies, the one Al Pacino sits on the steps in front of at the end of And Justice For All. It felt good seeing it, it being so familiar and all. Kind of like meeting an old friend.

Only it wasn’t the Criminal Court Building. It was a court build

ing, but it wasn’t the Criminal Court Building. At least it wasn’t 111 Centre Street. It was 60 Centre Street, and it was the Supreme Court. The Criminal Court Building turned out to be a building two blocks up the street. I didn’t know that, because it had never been in any movies, and the reason it had never been in any movies was because it was just your ordinary, tall, rectangular building, just like any other office building, and what movie director in his right mind would want to film there when he could wheel his camera around and shoot the sucker with the marble steps on down the street?

Not only that, The Criminal Court Building wasn’t 111 Centre Street either. It was 100 Centre Street. 111 Centre Street was a building of no distinction whatsoever across the street.

Which really bummed me out. Which was silly, of course. Because once you get inside, one building is just like another, and what difference could it possibly make anyhow? I guess it was just that I was still so miffed about having to serve at all that I was programmed to be bummed out. That and the fact I somehow sensed that this was just the first of a series of disappointments.

As I said, my jury duty summons told me to report to Room 362 on the third floor. I did, and found a large assembly room with a bunch of seats all facing forward and a counter up front. About twenty people were already there, milling around, sitting in the seats, reading newspapers and drinking coffee from the concession stand downstairs or from the coffee machine in the front of the room.

There was a woman behind the counter, and I wondered if I should go up to her and hand her my summons. A sign on the counter said please do not approach this desk during roll call. Which immediately made me feel stupid if what I thought was a counter was really a desk. It certainly looked like a counter. Whatever it was, I wondered if I should approach it. It certainly didn’t look like roll call, which I assumed wouldn’t be until ten o’clock.

While I was standing there thinking all this, a man went up to the counter or desk or whatever, and handed his summons to the woman behind it. When she appeared to accept it, I figured maybe that was the thing to do. I walked up to the counter and waited until she’d finished with the man. When she had, I handed her my slip.

Clicker Training

Clicker Training Lights! Camera! Puzzles!

Lights! Camera! Puzzles! The KenKen Killings

The KenKen Killings 12-Scam

12-Scam The Puzzle Lady vs. the Sudoku Lady

The Puzzle Lady vs. the Sudoku Lady 2 Murder

2 Murder 7 Shot

7 Shot You Have the Right to Remain Puzzled

You Have the Right to Remain Puzzled Puzzled to Death

Puzzled to Death 11-Trial

11-Trial The Witness Cat (Steve Winslow Mystery)

The Witness Cat (Steve Winslow Mystery) With This Puzzle, I Thee Kill

With This Puzzle, I Thee Kill The Anonymous Client sw-2

The Anonymous Client sw-2 Death of a Vampire (Stanley Hastings Mystery, A Short Story)

Death of a Vampire (Stanley Hastings Mystery, A Short Story) The Wrong Gun sw-5

The Wrong Gun sw-5 NYPD Puzzle

NYPD Puzzle 6 Juror

6 Juror 07-Shot

07-Shot 04-Strangler

04-Strangler 02-Murder

02-Murder SW04 - The Naked Typist

SW04 - The Naked Typist Actor

Actor The Naked Typist sw-4

The Naked Typist sw-4 Presumed Puzzled

Presumed Puzzled SW01 - The Baxter Trust

SW01 - The Baxter Trust SW06 - The Innocent Woman

SW06 - The Innocent Woman SW02 - The Anonymous Client

SW02 - The Anonymous Client Caper

Caper 4 Strangler

4 Strangler The Underground Man sw-3

The Underground Man sw-3 Manslaughter (Stanley Hastings Mystery, #15)

Manslaughter (Stanley Hastings Mystery, #15) A Puzzle to Be Named Later--A Puzzle Lady Mystery

A Puzzle to Be Named Later--A Puzzle Lady Mystery 05-Client

05-Client 16 Hitman

16 Hitman SW05 - The Wrong Gun

SW05 - The Wrong Gun 3 Favor

3 Favor Last Puzzle & Testament

Last Puzzle & Testament The Purloined Puzzle

The Purloined Puzzle 03-Favor

03-Favor SW03 -The Underground Man

SW03 -The Underground Man The Innocent Woman sw-6

The Innocent Woman sw-6 10 Movie

10 Movie 06-Juror

06-Juror Puzzled Indemnity

Puzzled Indemnity Arsenic and Old Puzzles

Arsenic and Old Puzzles Dead Man's Puzzle

Dead Man's Puzzle Safari

Safari $10,000 in Small, Unmarked Puzzles

$10,000 in Small, Unmarked Puzzles The Baxter Trust sw-1

The Baxter Trust sw-1 5 Client

5 Client Cozy (Stanley Hastings Mystery, #14)

Cozy (Stanley Hastings Mystery, #14) Blackmail

Blackmail A Puzzle in a Pear Tree

A Puzzle in a Pear Tree A Clue for the Puzzle Lady

A Clue for the Puzzle Lady Clicker Training (Stanley Hastings Mystery, A Short Story)

Clicker Training (Stanley Hastings Mystery, A Short Story) Detective (Stanley Hastings Mystery Book 1)

Detective (Stanley Hastings Mystery Book 1) 13 Suspense

13 Suspense